The tallest peak outside the Himalayas presented itself as an obvious challenge to a novice mountaineer like myself in 2009. A technically easy summit, Aconcagua is spiced with the dangers of extreme weather and altitude.

At the time the mountain was under some notoriety as the month before it had claimed five lives. As I made final equipment checks in Buenos Aires, the TV looped video showing the last steps of one unfortunate, a mountaineering guide with much experience on Aconcagua. He was suffering from altitude sickness and the party of rescuers that had found him were unable to coerce him into descending and they themselves unable to carry him down from an altitude of seven kilometres into the sky.

The next day I arrived into the city of Mendoza and met up with our guides and my fellow group of climbers. From there we travelled up into the Andes to an off-season ski hotel in Villa de los Penitentes, at 2600 metres above sea level. Several of the group were already feeling mild effects of the altitude here, rapid breathing and headaches. We spent our final night in a bed after a beef and wine supper.

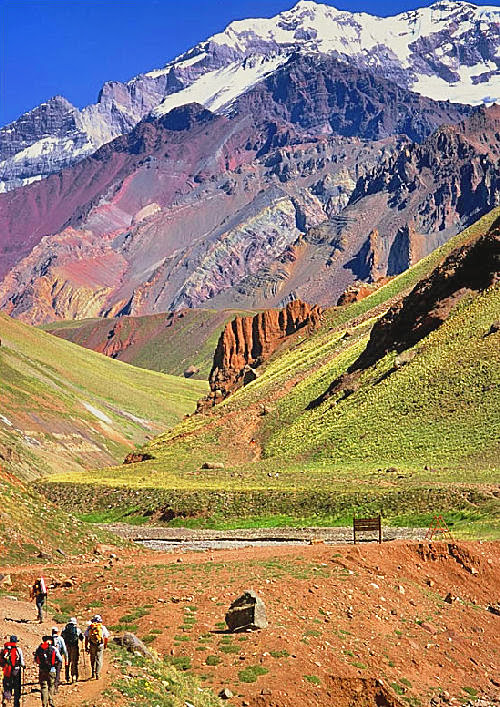

As the sun rose we travelled to the park entrance and set feet down at the rangers station and then set out on the seven kilometre walk to ascend the 450 metres to our first camp, Confluencia. We crossed the Horcones river on a charming rope bridge built by the crew of ‘Seven Years in Tibet’ for Brad Pitt and David Thewlis before arriving into camp.

Over the next days we acclimatised to the altitude and moved to the final base camp, Plaza de las Mulas at 4900 metres above sea level. Until this point all movement had been along valley floors and gradient lines. Now at the base of the mountain the summit blocked the midday sun above our heads, from here it would be all vertical.

Acclimatising to the altitude means taking lots of siestasFor a low-plains drifter such as myself, ascending a mountain requires physical adaptation. Your body needs to produce more red blood cells and capillaries to carry more oxygen around the body. The body also needs more hydration, some seven to eight litres of water a day. The fresh melt water up on the mountain is so pure that drinking it makes you ill. It lacks the minerals and ions that the body needs and washes your body of these minerals and ions through reverse osmosis. To combat this tea or Tang is added to the water. Tang being the powdered flavour popularised by its use in the NASA space programs. Force feeding yourself eight litres of Tang a day soon leads to a life-long aversion to the sickly, sweet drink.

A picturesque base-camp in good weatherOnce acclimatised the vertical ascent begins, which is very Duke-of-York. There are three main camps on the face of the mountain after base camp. Each day you have to ascend to next camp location, bury your extra equipment under rocks, descend back to the earlier camp and sleep. Then the following day return to the next camp to continue. So for the 3 camps another 6 days of up and down until you can try to summit.

The beginning of a long day’s climbThese ascents are tough and slow even under good conditions. The group starts out in single file with next camp visible high on the mountain’s shoulder nestled in a crag. The path are long zigzags with difficult footing. The guide keeps the same pace to preserve the group’s energy, becoming seemingly more rapid towards the end. The destination, always in sight, never seems to get nearer and during these interminable steps the group is quiet. Thoughts wander and the subconscious doubts your ability to get to the top. It doubts your credibility in being on the mountain and questions decisions in life. Four hours, eight hours, the camp seems to near. The pace is unchanged, but now becoming more insistent, each step part of an perpetual bleep-test.

The camps can be quite exposedAt sunset on the eighteenth day we reached the second camp on the mountain face, Nido de Condores. We were already the highest thing around, no other mountain peak rivalled our position. The only interruption in our 360 degree view of the top of the world was the summit of Aconcagua itself above us. As I looked around I was astounded by what I saw.

Everything was in perfect focus. Many kilometres down to the valley bottoms and away to the lower steppes, other inferior peaks, rocks and ice were all bathed in the sunset’s palate of colours. Deep magentas, rich ambers and vivid fuchsias bled across the immense landscape like a gargantuan chromatography experiment. It was unforgettable, a sight that was the herald to the storm which ended our attempt to summit Aconcagua.

The beauty of the AndesOnce the night came we had the tents erected then the wind blasted through our camp. The guides ordered us to stay on lock-down in our tents so we would not wander off to a grisly fate in the blizzard. At five and a half kilometres above sea level much of the group suffered from altitude sickness with symptoms of migraines and vomiting. To illustrate just how cold is wind chill factor -30 Celsius, a fresh bag of vomit takes less than ten minutes to freeze. Any bare skin left exposed out of the sleeping bag later wakes you up with a burning numbness.

A storm cloud passes the summitWe awoke to a calm day, but the forecasts radioed up to us from base camp were predicting more storms. We had used all our bad-weather days at lower camps. The guides gathered our group together and had us make a choice. Either we advance today up to the next and final camp risking more severe altitude sickness but with the slim possibility that the storms may pass us by. Or we appreciate the effort we had made so far, a full kilometre higher in the sky than any Alp, and take in the amazing view for a while before packing up and returning to base camp.

There was much discord among the group, We took the giudes aside and asked them for their opinion. They said that the storms were certain to come and put us at risk, their choice would be to descend. We chose to descend. Even though it was our investment and opportunity being washed out by the storms, the guides know the mountain and everyone respected their opinion.

Supplies are bought in each morning, injured or worse climbers are taken awayWe packed up and took in the incredible view and made our peace. The return journey at lower altitudes was notably easier, the long trek out of the park effortless . We skipped the final 35 kilometres over rough terrain to return to our first glimpse of a road in 3 weeks. Back in the city of Mendoza every breath of air was a dizzying oxygen high. We felt invincible and attacked the wine and the steak we had been denied the previous weeks. We were summit-less though still felt accomplished.

A mule train returning to the park entranceToday the mountain, the sentinel, awaits for us to decide when we shall return to finally reach the summit. If only I could find my bloody boots.

Our intrepid team, minus guides. Bertie Chamberlain, Ralph Rogge and Richard Townley.